“By the pricking of my thumbs,

something wicked this way comes.”

(William Shakespeare, Macbeth)

And if there’s anything even more memorable about this already thrilling time of the year, it’s that even the air outside smells like trouble and mischief.

Halloween is at the door, knocking incessantly to be let in; therefore, dear reader, prepare yourself, and let’s get this party started.

Everybody knows that Halloween falls on October 31st, but while some people know about its mysterious origins, most of them have never even heard the word ‘Samhain’ nor do they know how influential this Celtic festival has been for our hallowed and frightening fête. Being one of the most popular celebrations observed across the globe, All Hallows’ Eve is mainly associated with dressing up in scary costumes, trick-or-treating, and carving pumpkins. And although there are some similarities with its predecessor, the roots of what became the most terrifying night of the year are indeed quite different.

The term ‘Samhain’ (pronounced SOW-in or SAH-win) derives from Gaelic and can be roughly translated as “Summer’s End”. It was an agrarian festival celebrated by the ancient Celts during the Iron Age (1200 BC-600 BC circa) that lasted about three days, held halfway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice, when it was believed that the barrier between the mortal world and the Otherworld was bridged and that the spirits of the dead could freely roam the earth. Samhain is in modern Irish (Gaelige) the name for the month of November, while the contemporary Irish term for Halloween is ‘Oíche Shamhna’, which means ‘The Eve of November’ or ‘November Night’. The exact date of Samhain is uncertain and remains a subject of controversy, partly due to the Roman Catholic Church’s introduction of the Gregorian Calendar in 1592, which obscured earlier important dates and shifted the entire timeline of our history. There are many debates about Samhain, particularly for its duration. Some state that it was held—like I already wrote—for three days, while others state that it took the entirety of the month of November. Unfortunately, we have no official records of Samhain festivities to prove these allegations, primarily because of the fact that Druids (religious leaders of the Celts who oversaw the rites) left no written records of their practices. They passed down their knowledge through a strictly oral tradition, making the writings we have on their account (most from early Roman writers who did not condone their culture) not reliable. We do have descriptions of the fête appearing in some early Irish works; however, these were written after the rise of Christianity in Europe, making them once again not completely trustworthy. Either way, we can only assume that at least the Samhain we know of today is partially based in truth.

In fact, if there’s one thing we can say for certain about the ancestor of Halloween is that this festivity marked a pivotal point in the Gaelic calendar. The ancient Celts divided the year into two halves—a lighter one and a darker one—and held four celebrations to mark the changing seasons: Imbolc (halfway between the winter solstice and spring equinox, supposedly on February 1st), Beltane (halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice, supposedly on May 1st), Lughnasadh (halfway between the summer solstice and autumn equinox, supposedly on August 1st), and Samhain (halfway between the autumn equinox and winter solstice, supposedly on November 1st). Of these four sacred times, Samhain is generally and usually regarded as the most important one for the Celts, as it is believed that it represented their New Year—a time of harvest, yes, but also a time of uncertainty and vulnerability in the face of the cold and unforgiving winter. As a matter of fact, one of the elements highly associated with Samhain is, of course, bonfires. Historian Geoffrey Keating (1569-1644) said in fact in work titled “The History of Ireland” that all fires were to be extinguished at the start of Samhain and that the Druids would light a new bonfire, into which the bones of animals would be tossed (‘bone-fire’), and then from that flame, people would light their torches and carry them home to relight their own hearths to bring light into the new year. These are all deductions, but many are the historians who believe that the celebrations also included animal sacrifices (although there is no shortage of accusations of human sacrifices), feasting, dancing, and the practice of wearing costumes made from animal skins and, perhaps, even animal heads.

The predecessor of Halloween is also deeply intertwined with Celtic mythology, like in the 10th-century tale of Tochmarc Emire (The Wooing of Emer), where Samhain is listed as the first of the four seasonal festivals of the year. Or in the tale of Echtra Cormaic (Echtra’s Adventure), where it’s said that the Feast of Tara was held every seventh Samhain. Or, again, in the story of Togail Bruidne Dá Derga (The Destruction of Dá Derga’s Hostel), where King Conaire Mór meets his death on Samhain, and many others. It is also believed that during this time of the year the Aos Sí or Sídhe—magical beings sometimes described as faeries, which I talked about in my article about the fae folk—entered freely into our mortal world from the Otherworld, a realm coexisting with our own. In later Christian times it was popularised the idea that the dead and the Sídhe would run amok and cause mischief on Samhain if they weren’t placated and paid the proper respect. So how did they do that?

Offerings and sacrifices played a major role during this frightening night. The offerings included cakes and even milk, while animal sacrifices were made to ward off evil. Divination was also extremely important during the celebrations, as the Druids were well-known to perform it, and Samhain has been associated with it for a long time. Then we have mumming and guising, of course, but of how Halloween came to be I delve deeper in my All Hallows’ Eve article. And then, lastly, the coming of the dead. Like I said, Samhain was seen as a liminal time during which the veil between life and death blurred to nothing. Where the Aos Sí were feared, the departed, instead, were honoured. The souls of the dead were thought to revisit their homes, seeking hospitality. So, it was common to set a place for them at the dinner table and light candles in the windows to help guide them back home.

Now, even though Samhain has transformed drastically over the centuries, merging with All Hallows’ Eve and evolving into the beloved and despised fête of Halloween, many pagan and neo-pagan religions still honour and practise it today. From parades and dressing up to paying respect to your ancestors or carving pumpkins, Halloween truly is and remains a one-of-a-kind festivity. Whether you call it Samhain, Halloween, or All Hallows’ Eve, it’s a moment where the ordinary meets magic, and, I don’t know about you, dear reader, but it makes me absolutely thrilled.

I don’t know if you’ve already chosen your costume for this year, but either way, beware, dear reader. Beware, because, just as the words I began this article with say, something wicked is indeed coming, and when the veil grows thin tomorrow night… well… good luck.

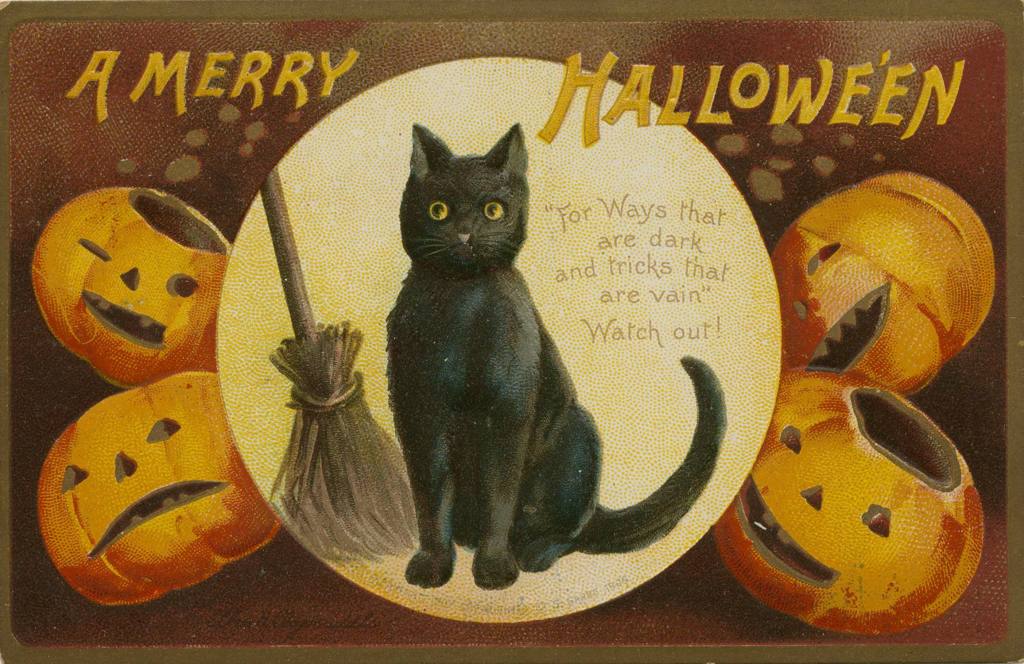

Up, A Merry Hallowe’en by Ellen H. Clapsaddle (1909)

Sources:

Samahain: The Roots of Halloween by Luke Eastwood (2021)

The Celtic Origins of Halloween

Penny for your thoughts…