“You must wake and call me early, call me early, mother dear;

To-morrow ’ll be the happiest time of all the glad new-year,

Of all the glad new-year, mother, the maddest, merriest day;

For I ’m to be Queen o’ the May, mother, I ’m to be Queen o’ the May.”(Alfred, Lord Tennyson, The May Queen)

The title May Queen or Queen of May evokes both a mythical figure of the season and the living embodiment of May Day, the festival that welcomes the first of May.

Nowadays, this celebrated monarch is typically represented by a teenage girl, selected by her school or community and often through a vote by her peers, to commence the May Day parade and celebrations.

To be chosen means not only to have a great role but also to hold great responsibility. And although it is the dream of lots of girls, only one is crowned queen.

The May Queen is traditionally robed in a flowing white gown, a symbol of purity, with a delicate tiara adorning her head. The most important thing, however, is that this selected girl needs to especially represent springtime.

And that is why, apart from a gown and a crown, this young lady needs to be basically covered in flowers.

From garlands to bouquets to just petals—everything must be floral.

It’s a very enchanting and romantic contemporary custom, but if we look back in history, where exactly does it come from?

The Queen of May tradition, like most things in this blog, comes from ancient pagan spring festivals, which celebrate fertility and renewal. She is purity, strength, and growth, as plants and flowers are during this period of the year, and she is one of the many embodiments of our Earth’s life force and spirit.

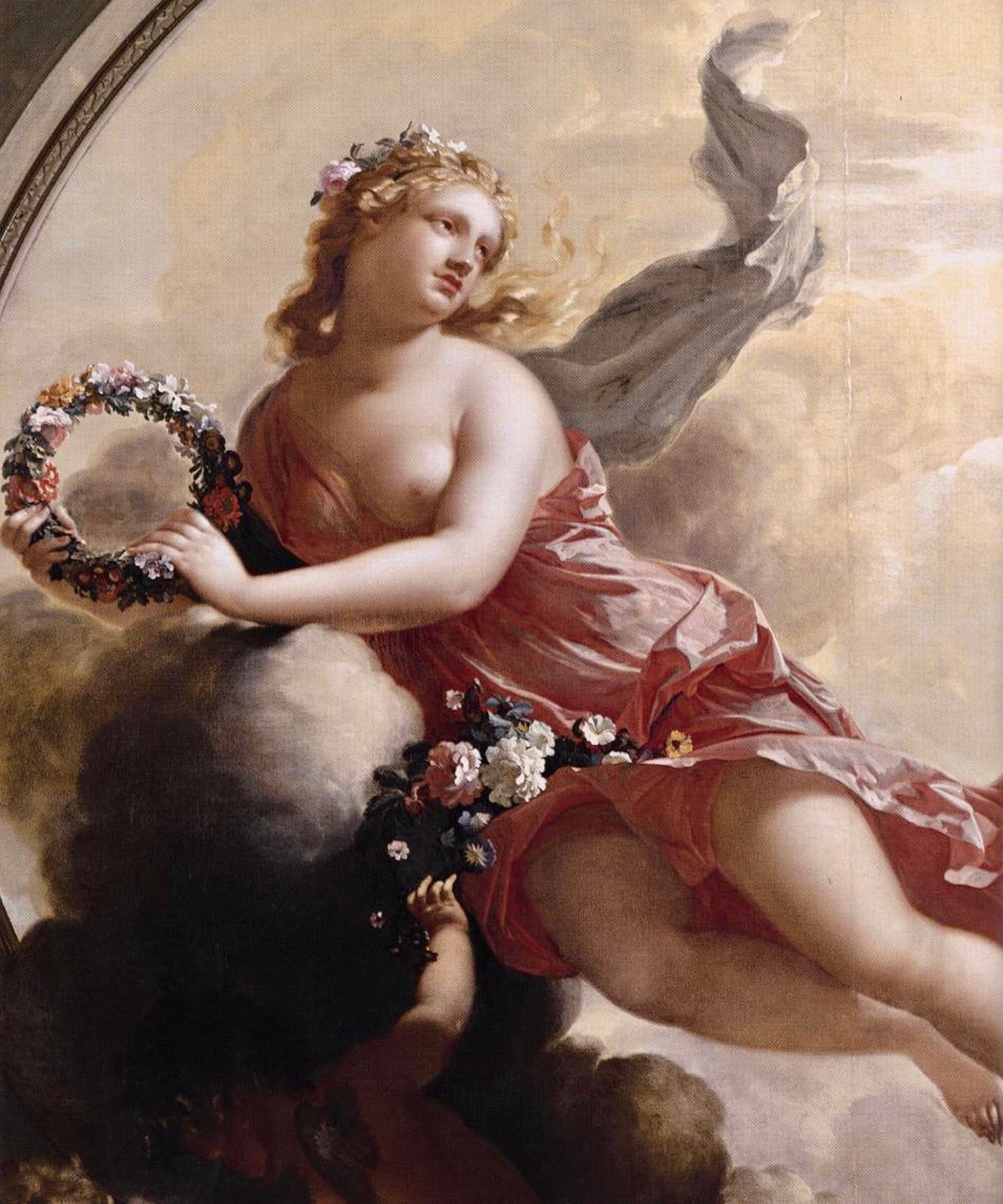

It is also believed that, although with no actual academic support, the May Queen is indeed linked to Maia or Flora, the Roman goddesses of springtime; to the Virgin Mary, as the month of May in Christian beliefs is associated with her figure; and to Maid Marian, the young village girl in the English folktales of Robin Hood.

This pagan fête is and was the way people honoured nature’s rebirth in the past. Something that, although differently, we still very much do today. It is then no one’s surprise that once upon a time New Year’s Day was, in fact, in spring.

But, oh well.

The Queen of May tradition then was, of course, adopted in the mediaeval and later Victorian times, becoming even more popular.

During the Middle Ages, the May Queen observance evolved as Christianity spread and while many seasonal holidays and commemorations were reinterpreted to fit ecclesiastical canons. It is said that, much like nowadays, villages would choose a young woman to lead the celebrations, which included a maypole dance and obviously lots of feasting.

In the Victorian era, instead, it was revived and romanticised mainly for the growing interest in folklore and rural customs. Victorians adored nature and the idea of innocence; therefore, the May Queen, during those times, became a whole community event, tied to their loved ideals of purity and femininity.

Not far off from how we honour it today.

You could then say that this enigmatic and charming practice was primarily born in Europe. It is often believed that it mainly comes from the British Isles; however, as Jacob Grimm, from the Brothers Grimm, proves, it could be far older and more meaningful than we realise, echoing rituals long buried in time.

Jacob Grimm wrote an extensive collection of Teutonic mythology in his life, and in one of his works, he talked about how in the French province of Bresse—now called Ain—there was a custom in which a young girl was chosen to be May Queen.

Therefore, as I already said, it could be far older and more meaningful than we realise.

In modern and neo-pagan paths, the Queen of May plays a central role in the celebration of Beltane—one of the eight sabbats on the Wheel of the Year, marking the midpoint between the spring equinox and the summer solstice. (Don’t worry, I’ll make an article on that as well.)

Beltane is a fertility festival, deeply rooted in ancient Celtic and pre-Christian traditions that, much like May Day, honours the life force of nature, the renewal of the land, and the sacred union of opposites.

Historically, it was celebrated with bonfires, lots of food, and rituals to bless the land, animals, and crops. The May Queen is an important icon during Beltane, and she is also frequently paired with the Green Man or May King, a wild, virile figure, representing the masculine force.

The union between the Queen of May and the Green Man also represents the Sacred Marriage, a powerful expression of balance, creation, and harmony between earth and sky, feminine and masculine, human and nature.

It was, therefore, a moment of immense importance.

Today, we may dance around a maypole, decorate everything with flowers, light fires, and honour the passion and vitality of springtime, thinking that we are so different from the ancients. And yet, with even a brief glimpse into the past, we may find that we are far more alike than we imagine.

After all, being one of my favourite months of the year, it truly feels like May is the perfect period to focus on joy, love, connection, and the blossoming of life, both in nature and in ourselves.

What better season to surrender wholly to love? It is, I believe, the time for nothing else.

Up, Flora with Putti Strewing Flowers by Adriaen van der Werff (1696)

Sources:

Penny for your thoughts…