“To die will be an awfully great adventure.”

(James Matthew Barrie, Peter Pan and Wendy)

All children, except one, grow up.

He flies through nursery windows, battles pirates, communes with fairies, and lives forever in a place called Neverland. I’m sure you all know who I’m talking about, because while Peter Pan refused to grow up, his story most certainly has.

Peter Pan is not just a character. He is a symbol, an idea, and a contradiction, created in the early 20th century by Scottish playwright and novelist James Matthew Barrie. And since then, he has transcended the page and stage, becoming one of the most iconic and complex figures in children’s literature and beyond.

The infamous ‘boy who never grew up’ first appeared in Barrie’s 1902 novel The Little White Bird, in a few short chapters later published separately as Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906). But it was in the 1904 stage play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up, and its 1911 novel adaptation, Peter Pan and Wendy, that the character fully took flight.

Inspired by Barrie’s deep friendship with the Llewelyn Davies boys, he was not born from magic and imagination alone but from grief, nostalgia, and a fascination with childhood’s impermanence. Barrie, who never had children of his own, was haunted by time’s passing. Therefore, in Peter, he imagined a boy who would never have to leave the dream.

The story begins one night in London, where Peter Pan, a mischievous flying boy, visits the nursery of Wendy, John, and Michael Darling. With the help of fairy dust and his companion Tinker Bell, he teaches the three siblings to fly and takes them to Neverland (fun fact: in Italian it’s The Island that Doesn’t Exist), a magical island filled with mermaids, fairies, Lost Boys, and pirates. There, they embark on fantastical adventures, including battles with the villainous Captain Hook and his crew. Wendy takes on the role of a mother for her two brothers and the Lost Boys, while Peter remains carefree and forgetful throughout the story, resisting change and responsibility. Eventually, however, the Darling children choose to return home, understanding that growing up is inevitable. But Peter, unchanged and unwilling to let go, stays behind in Neverland, forever as the boy who wouldn’t grow up.

I’ve been in love with J. M. Barrie’s tale since I was a child. I remember being so fascinated and intrigued by the characters, the magic, and the entire island that I literally dreamt and wished upon a star to be able to fly there. I would always look for the second star to the right, but, somehow, I never managed to find it. Or I would always try to catch a glimpse of Captain Hook’s Jolly Roger in the moonlight, but, somehow, once again, I never did. My dream always remained just a dream, and so did Peter Pan’s life. The boy who refused to grow old.

Perhaps that’s why I liked and still like this story so much.

Having already written about fairies, mermaids, and pirates, it seemed only natural to conclude this hot July with an article about one of the most, in my opinion, enchanting fairy tales.

Wait… is it a fairytale?

Mm… well… for me it is. It has all the elements to be one, and it also has an exceptional moral, which changes based on the reader. Let me explain it better. Peter Pan is both light and dark. He is play and peril, innocence and danger. At a glance, he may just seem like the embodiment of youth: a boy who’s carefree, adventurous, and full of laughter and tricks. However, he is also forgetful, selfish, and wild in ways that unsettle. He forgets people after they leave, feels little remorse, and dances on the edge of cruelty. Peter is a reminder that eternal childhood is not just captivating. It’s unnatural. The duality of his character is extremely central to his story. He is not a hero in the traditional sense. Ha! He’s not even fully real in the world he inhabits.

Peter Pan, the true Lost Boy, is a metaphor made flesh and refusal given wings. He doesn’t simply represent that part of us that refuses to grow up but also that part of us that fears what we might lose if we do. Neverland is a reflection of his character and personality. It’s not just a fixed place. It shifts depending on who’s imagining it. For the Darling children, it’s an island of pirates and fairies. For Peter, it’s home. And for the reader, it’s a liminal space between dream and death. Time does not pass there in the usual way, and seasons do not change unless the story demands it, but when they do, it’s all because of Peter. The inhabitants of Neverland, like Tinker Bell and the Lost Boys, are also all mirrors of childhood’s archetypes. Even Captain Hook, with his ticking crocodile, represents the inevitability of time. Peter may fly fast enough to escape it, but the rest of us are not so lucky.

One of the characters that I want to analyse the most, however, is definitely Wendy Darling. Apart from her beautiful name, which I ardently wanted to have when I was little, she is a marvellous character. Where Peter is the refusal of time, she is the gentle acceptance. In the 2003 version (my favourite), the story starts with Wendy too refusing to grow up. The adults in her life tell her that she is becoming a woman, that she needs to leave the nursery, that she needs to stop sleeping in the same bedroom as her brothers, and that there’s even a ‘kiss’ waiting at the corner of her lips. But Wendy, like Peter, is still caught in the space between childhood and something just beyond it, so, at first, she too resists the pull of adulthood.

It is absolutely lovely to see her change throughout the tale. She arrives in Neverland not just as a companion but as a sort of mother figure. She stitches pockets, tells stories, and tries to bring order to the chaos of play, even if she also wants to fly, be loved by Peter, and stay young. Wendy’s eventual return to London, and her choice to grow up, is the emotional heart of the book. She lives, remembers, and passes her memory on. Peter, instead, forgets. He does visit her years later, but he no longer recognises her.

He remains, while she moves on. It’s the tragedy of Peter Pan. A boy stuck in time.

It’s truly an incredible novel, but let’s go on.

For all its charm, in fact, this story is not without criticism. The portrayal of Indigenous people in the original story and later adaptations has been rightly challenged as racist and stereotypical, reflecting the horrible colonial attitudes of the time. I won’t say, “Let’s ignore that part,” because ignoring doesn’t make it better and doesn’t solve anything. It’s disrespectful. Therefore. We need to acknowledge it, take responsibility, and do better.

I can’t pinpoint all the adaptations of Peter Pan, for there are dozens of them, but I can say that each version emphasises something different—like the adventure, the melancholy, the danger, or the wonder—and in each of them, Peter is sometimes romanticised, sometimes villainised, or sometimes even reimagined as a symbol of death itself. I remember a few years ago when it became a bit of a scandal, the idea of Peter Pan as an angel escorting children away to the afterlife. But anyway, it’s safe to say that the boy who never grew up is never just one thing, exactly like childhood.

It’s outstanding to think that more than a century later, this story continues to captivate us all. Perhaps it’s because we, too, have moments when we don’t want to grow up, and we act childishly. Perhaps we all long for a time before responsibility and before adulthood. However, as much as we may envy Peter, I think the novel also reminds us that growing up doesn’t mean the end of wonder. Our bodies may grow, but if we can remember how we felt when we were children, then the magic never ends. I guess it’s difficult to keep it in mind.

We may never see a Jolly Roger in the night sky and the moonlight, but we all remain children at heart. So, who knows? Perhaps one night a mischievous boy will knock on your window, asking you to fly away. And who knows? Perhaps you will be tempted.

In the meantime, however, off to bed. But remember, dear reader, in case you forgot… second star to the right, and straight on till morning.

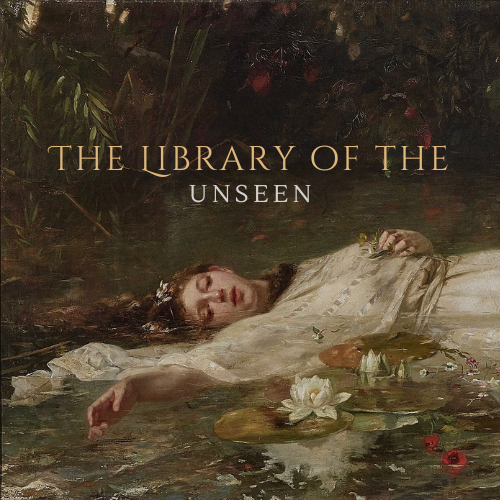

Up, Peter Pan Illustration by my amazing twin Soul

Sources:

Analysis of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan

Peter Pan: A Prime Example of Dark Children’s Literature

Coming of Age: Death in Peter Pan

The Little White Bird, or, Adventures in Kensington gardens by J. M. Barrie (1920)

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by J. M. Barrie (1918)

Peter Pan by James Matthew Barrie (2016) – a book in my library

Penny for your thoughts…